Melanin Matters - a photography workshop in Lagos, Nigeria

Glimpses at Coloristic Human Differentiation

As the visible surface of the human body, the skin is subject to cultural ascriptions and manipulations. The photography projects of the Melanin Matters week beautifully illustrate this.[1] The pictures presented below show a variety of meanings that are associated with skin and skin tone in Lagos, Nigeria. In doing so, they highlight some of the themes addressed by our research project on Coloristic Human Differentiation that examines the (de)thematisation, meaning and presentation of skin colour in everyday life, both in Nigeria and elsewhere. Our research project aims at developing a post-racial reconceptualisation of skin colour as a flexible marker of human categorisation and seeks to understand how and when skin tone becomes a marker of, for instance, ethnicity, class, gender, attractiveness, health or disability. In the following paragraphs, I am commenting on a selection of the photography projects, reflecting on them through the lens of our research project.

Kayode Oluwa’s photographs exemplify how the practice of boxing and the bodily work of boxers can leave traces on the body. A boxer can identify a fellow boxer by physical markers such as scars around the eye and rough knuckles. In Oluwa’s work, signs that are inscribed on the skin serve as markers for a form of athletic human differentiation. His project can also be linked to a sociological theory from 1995. The rough, hardened knuckles of the boxers in Oluwa’s photographs recall the bodily capital that Wacquant elaborated upon in his essay ‘Pugs at Work: Bodily Capital and Bodily Labour Among Professional Boxers’. Working with professional boxers in Chicago, he noticed that their bodies were central to their work. In addition to the three types of capital that Bourdieu identified in ‘Forms of Capital’ (1986) – economic capital, social capital and symbolic capital – their bodies seemed to represent a fourth form of capital. Alongside assets such as their network (social capital) and awards (symbolic capital), it was above all their bodies that gave them access to economic capital, i.e. financial rewards. Not only was physical effort required during a fight, but Wacquant noticed that the boxers were constantly working on their bodies in between fights. This work on the body was a central part of the boxers’ reality and everyday life. They tried to maximise their performance through training. In doing so, they had to be careful not to overdo it and suffer the injuries typical of their sport, such as a broken knuckle or hand. They also tried to boost their bodily performance before a fight through diet management and sexual abstinence so as to increase their chances of converting bodily capital into economic capital.

While some projects focus on scars, others zoom in on the marks that time and ageing leave on the skin. Odunayo Odedoyin’s photographs juxtapose images of the hands and faces of ‘young’ and ‘old’ Nigerians. This illustrates how time inscribes itself on the skin and how the skin can be used as a marker to categorise people by age: The observer categorises a person as ‘young’ or ‘old’ by evaluating aspects of the skin, such as its wrinkles or firmness.

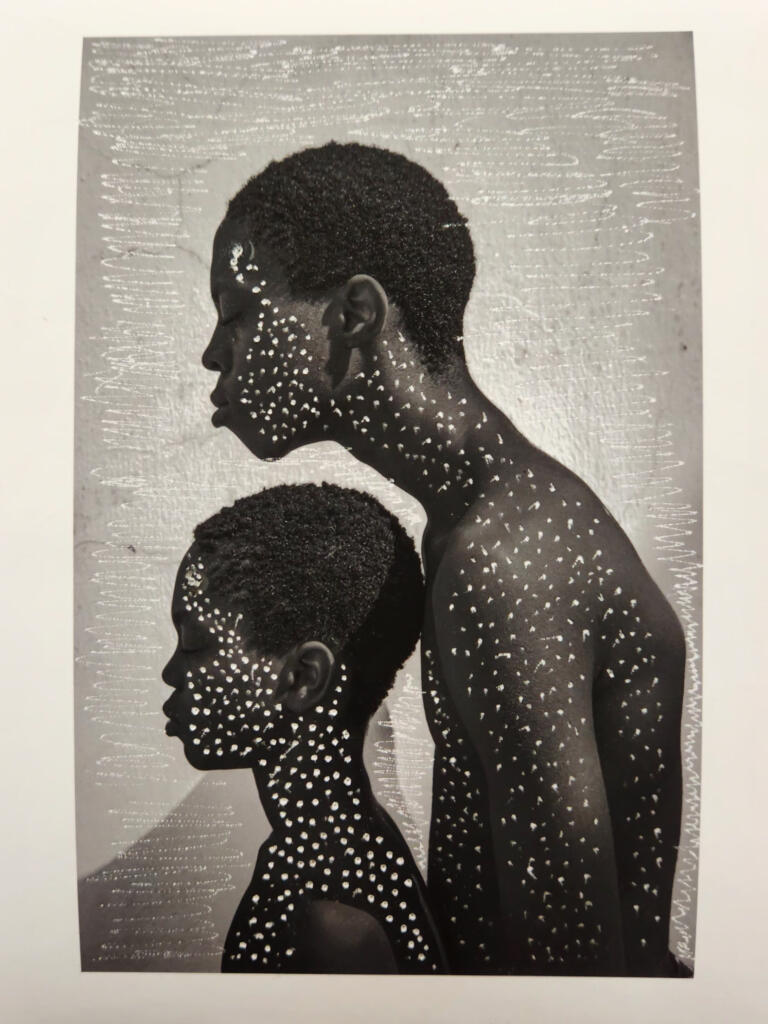

Noah Okwudini’s photo story explores body modification and the limits of what is human by telling a tale of transformation: An ‘old’ scientist slips into a ‘young’ shell and becomes a new, post-human being. The new shell is symbolised by a ‘young’ man with firm and wrinkle-free skin. What is interesting about this photo story is that the scientist’s transformation leaves a trace: The new post-human being has silver-shining skin. It raises the question of the limits of body enhancement by inscribing the transformation into the protagonist’s body and asks: Can we reinvent ourselves without leaving a trace of what was before?

Unwanted side-effects from attempts to modify one’s body also come to light in Oyewole Lawal’s work. Lawal shows how people who have lightened their skin can end up with the stigmatised marks typically associated with skin lightening. While some skin lightening practices may go unnoticed, side-effects are common among users of skin lightening products, especially when the products are used over a long period of time. Lawal chose to place images of the product packaging against the user’s hands. The darkened knuckles visible in the images are a typical side effect of hydroquinone, a chemical found in many skin-lightening products. They are an example of how attempts to modify the body can backfire. Skin lightening is a common but socially frowned upon practice in Nigeria. The knuckles show how the attempt to increase one’s social standing through lighter skin can have the opposite effect, i.e. how lightened skin can lead to stigmatisation instead of appreciation. It also addresses how the skin, as malleable as it is, can act against the will of its bearer, raising questions about the agency of the skin.

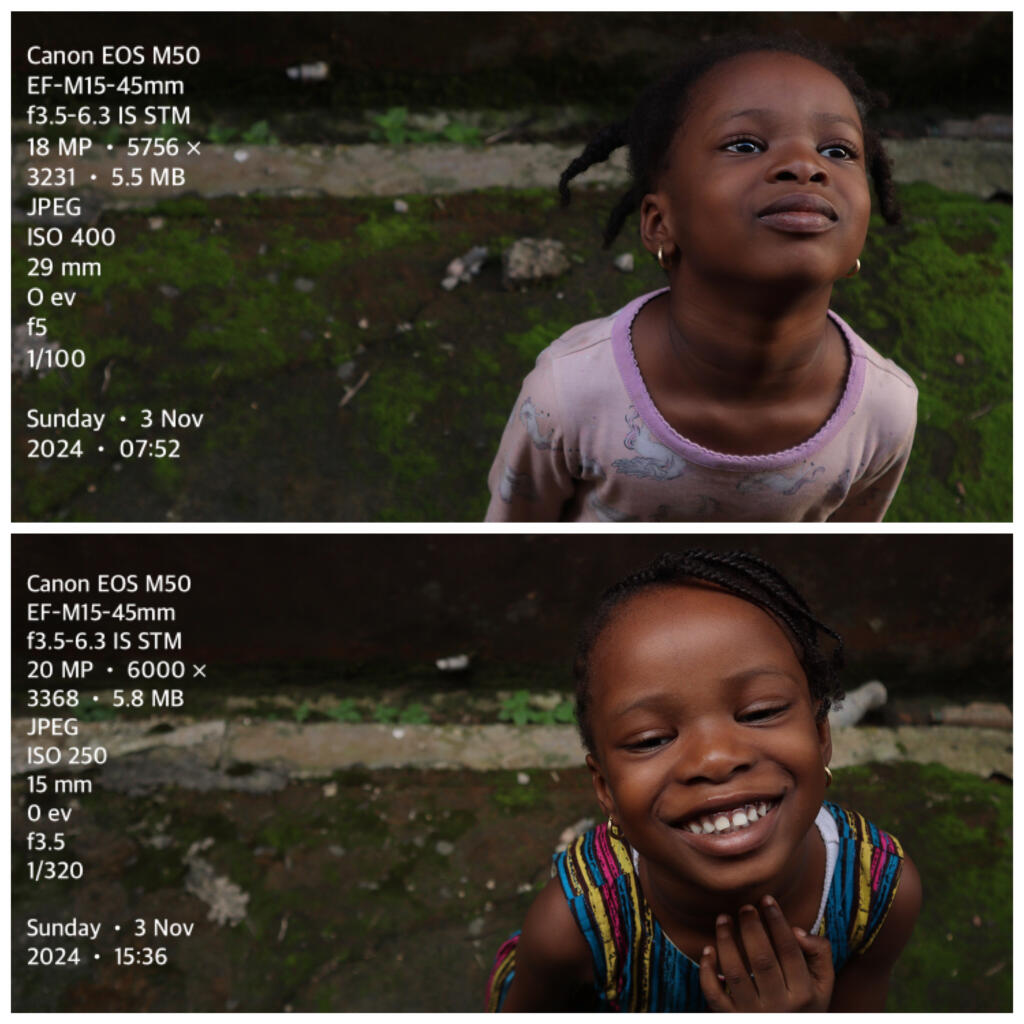

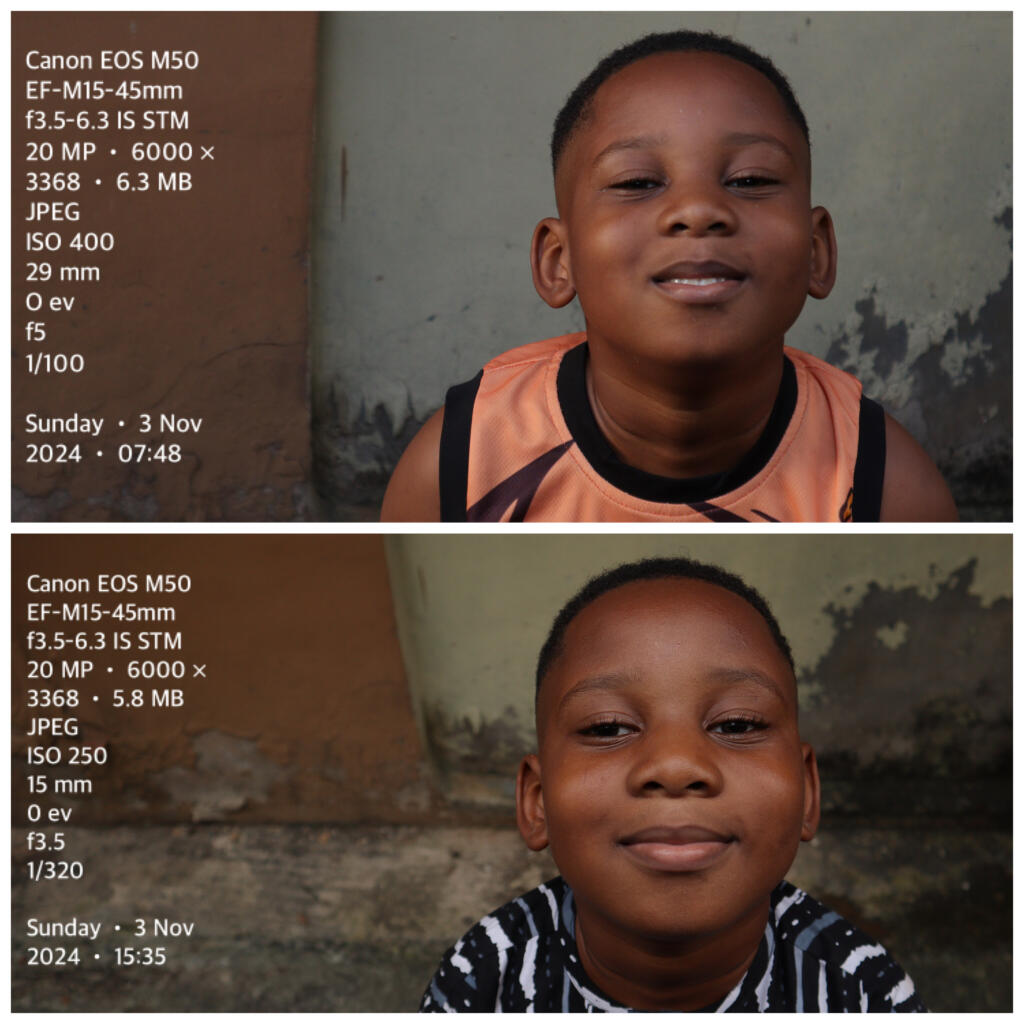

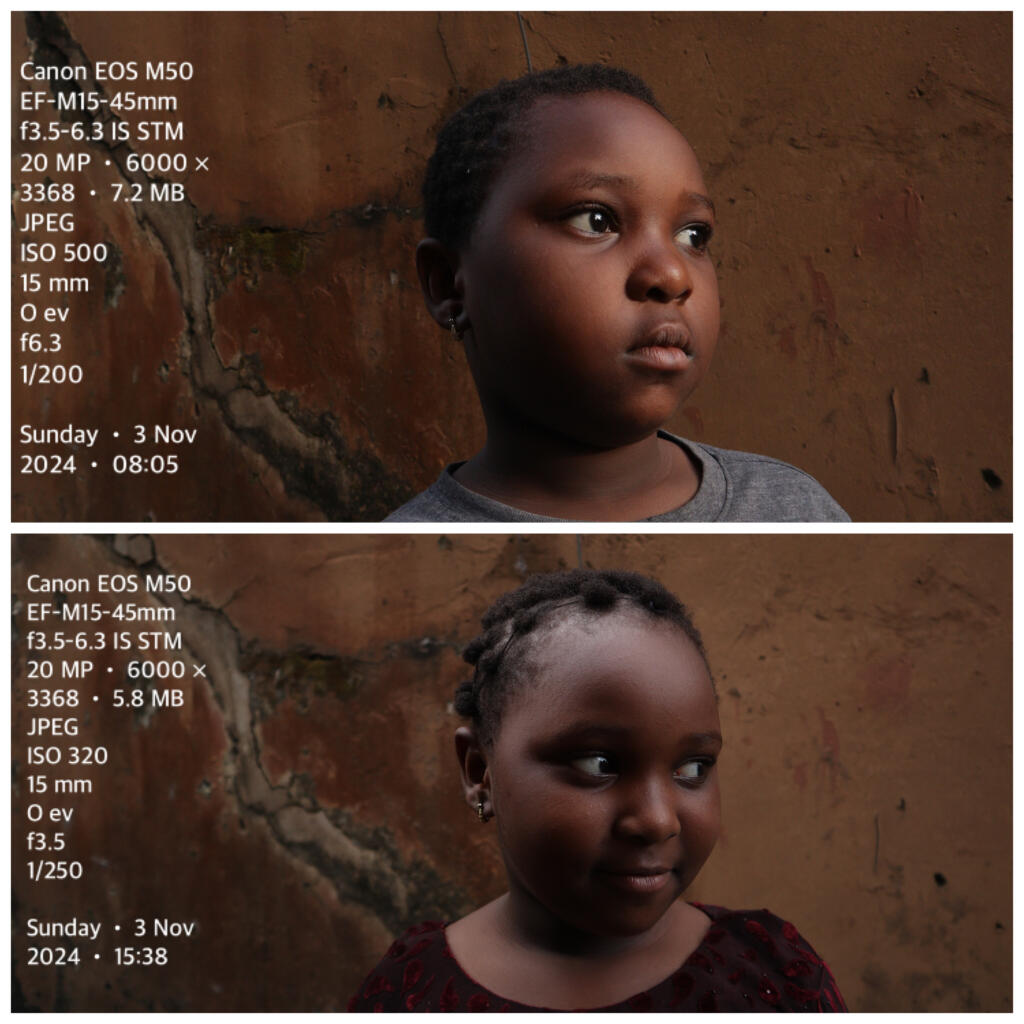

Olalade Lawal proposes a less common temporal contrast by showing morning and afternoon portraits of children. She demonstrates how one and the same person can have different skin depending on the context and circumstances. Considering this, how can we make statements about someone’s skin, when its texture, health, colour etc. is variable and highly dependent on aspects such as skin care, lifestyle or sun exposure? Skin not only changes over the years but is influenced by a multitude of other factors, leading to differences that can be observed over much shorter time spans. In our research project Coloristic Human Differentiation, one challenge in speaking about skin tone lies in its definition. When we speak about humans, do we portray them as having only one skin tone? If so, where do we find/locate it on the body? While people who regularly tan may see the sun-exposed parts of their body as representative of their ‘natural’ or ‘true’ skin tone, those who try to avoid tanning may refer to skin untouched by the sun as representative of it.

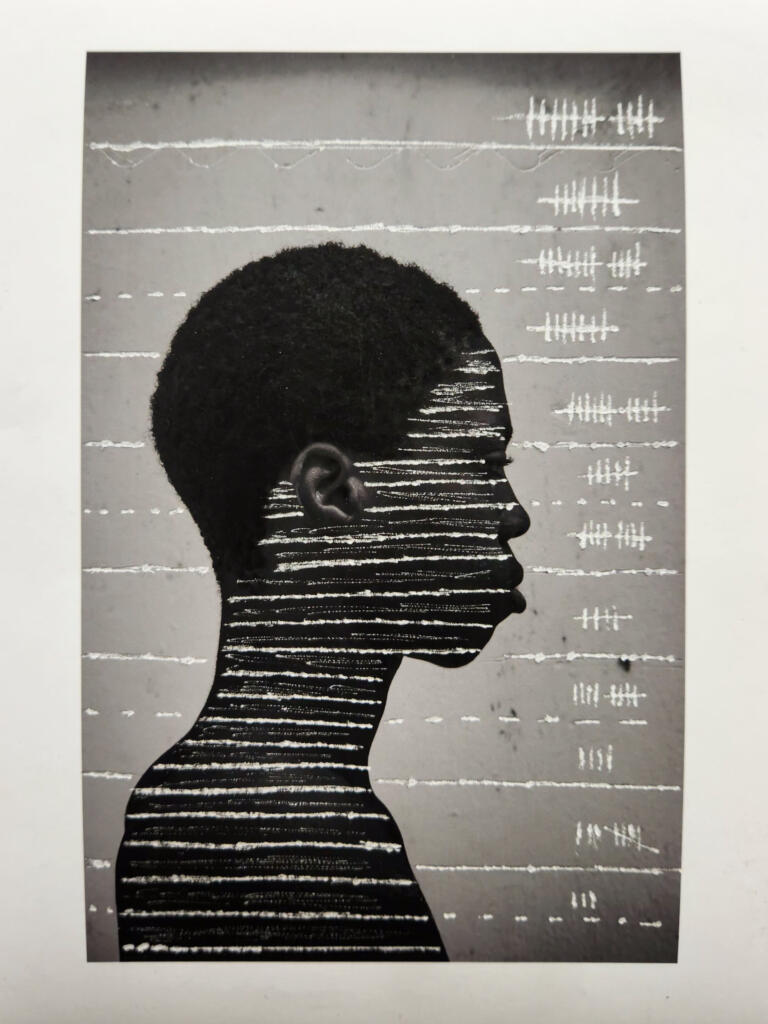

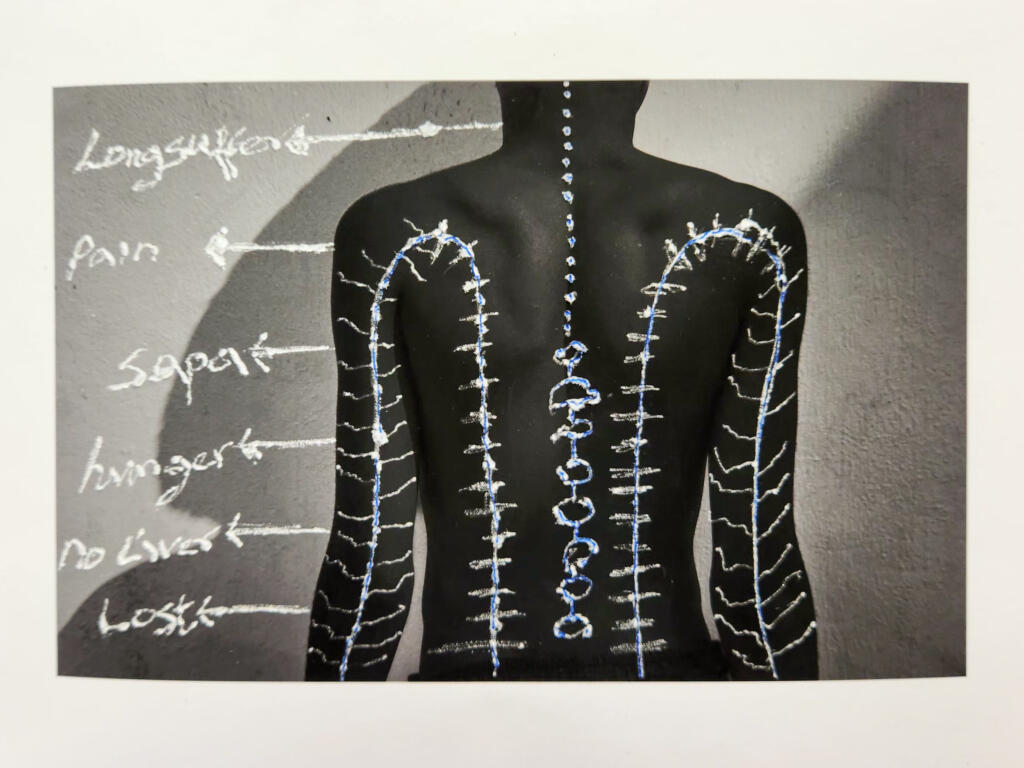

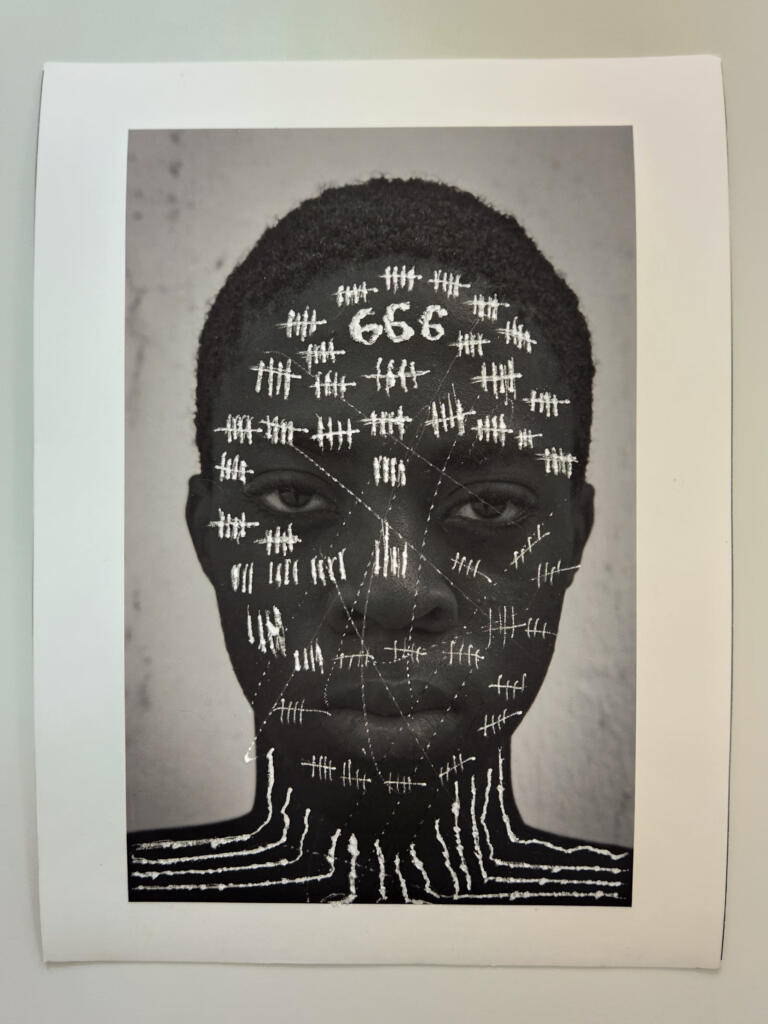

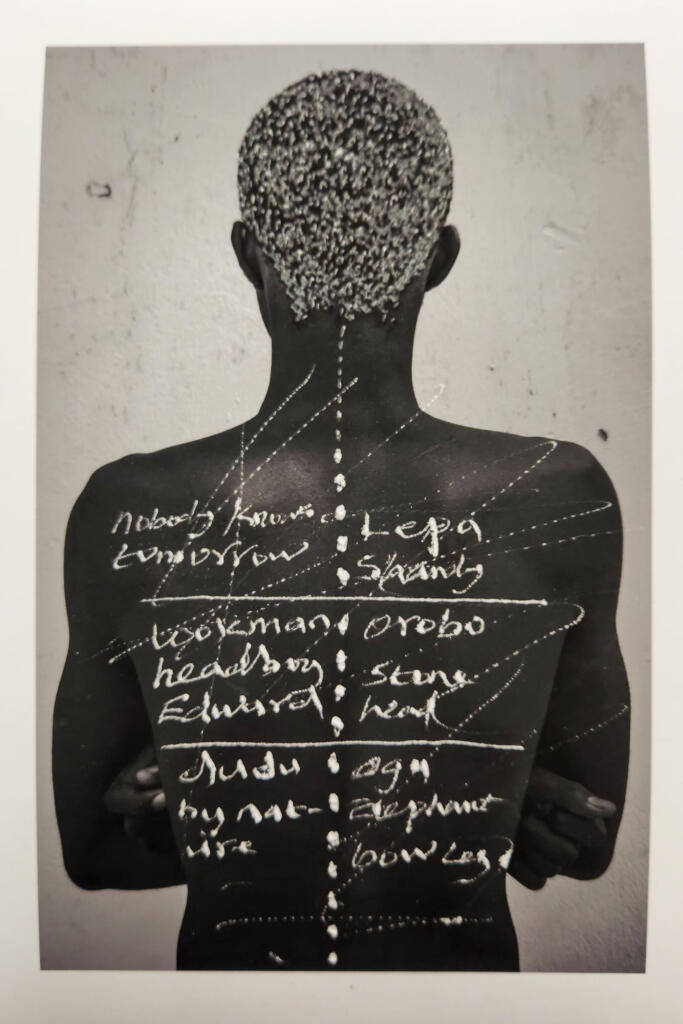

Neec Nonso and Mecca Akello make the invisible visible in their projects, choosing to address issues that lie beneath the surface through photographs that highlight the skin. Nonso used the material surface of printed photographs to carve into the skin of his depicted models. To show how he sees the Nigerian experience as being characterised by suffering and hardship, he marked the skin in portraits of his brothers. The results are X-ray-like images that bring internal scars and wounds to the surface, and thus to light.

Akello, as a darker-skinned woman, uses self-portraits to reflect on the ideals of beauty to which she has been subjected. Starting from her own skin, she provides a socio-cultural commentary and asks what beauty is in the Nigerian context – a question also raised by our research project on skin tone-based human differentiation. Her self-portraits explore how beauty is linked to lightness of skin: ‘But what is beauty’ shows the psychological distress caused by the slogans and names of lightening products. Other images show her drinking bleach, getting lightening injections, and scrubbing off her skin in an attempt to conform to the beauty ideal of skin-lightness. She starts and ends her series with images about advertising, beginning with the messages communicated by lightening products and ending with the place (or lack thereof) of darker-skinned women in advertising. She feels that darker-skinned women are underrepresented in the public space and in advertising. Through her self-portrait, she engages with the pain of feeling like it is not her place to be seen, to be in the spotlight. Akello’s photographs beautifully visualise central themes of our research project, namely what meanings are associated with skin tones in Nigeria, how they connect to other categorisations like gender and, lastly, what consequences there are on a personal and on a societal level of sorting individuals into skin tone categories.

[1] From the 29 October to 5 November, the CRC 1482 Human Differentiation, the Goethe-Institut Nigeria and the Nlele Institute jointly organized a photography workshop as part of the Melanin Matters week on skin and skin tones.

Literature

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. ‘Chapter 1: Forms of Capital.’ In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–58. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Wacquant, Loïc J.D. 1995. ‘Pugs at Work: Bodily Capital and Bodily Labour among Professional Boxers.’ Body & Society 1 (1): 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/135703. . ..