Exhibition "Sorting People"

Type Case

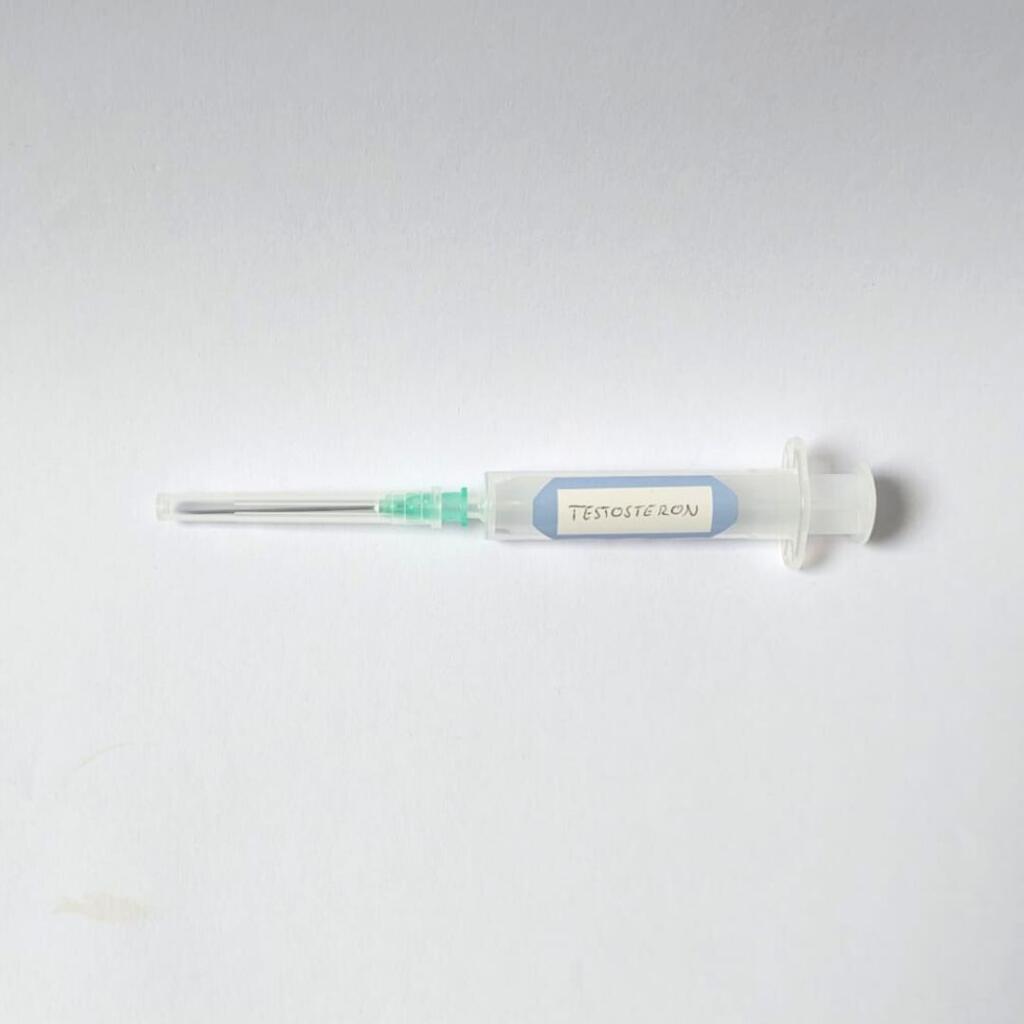

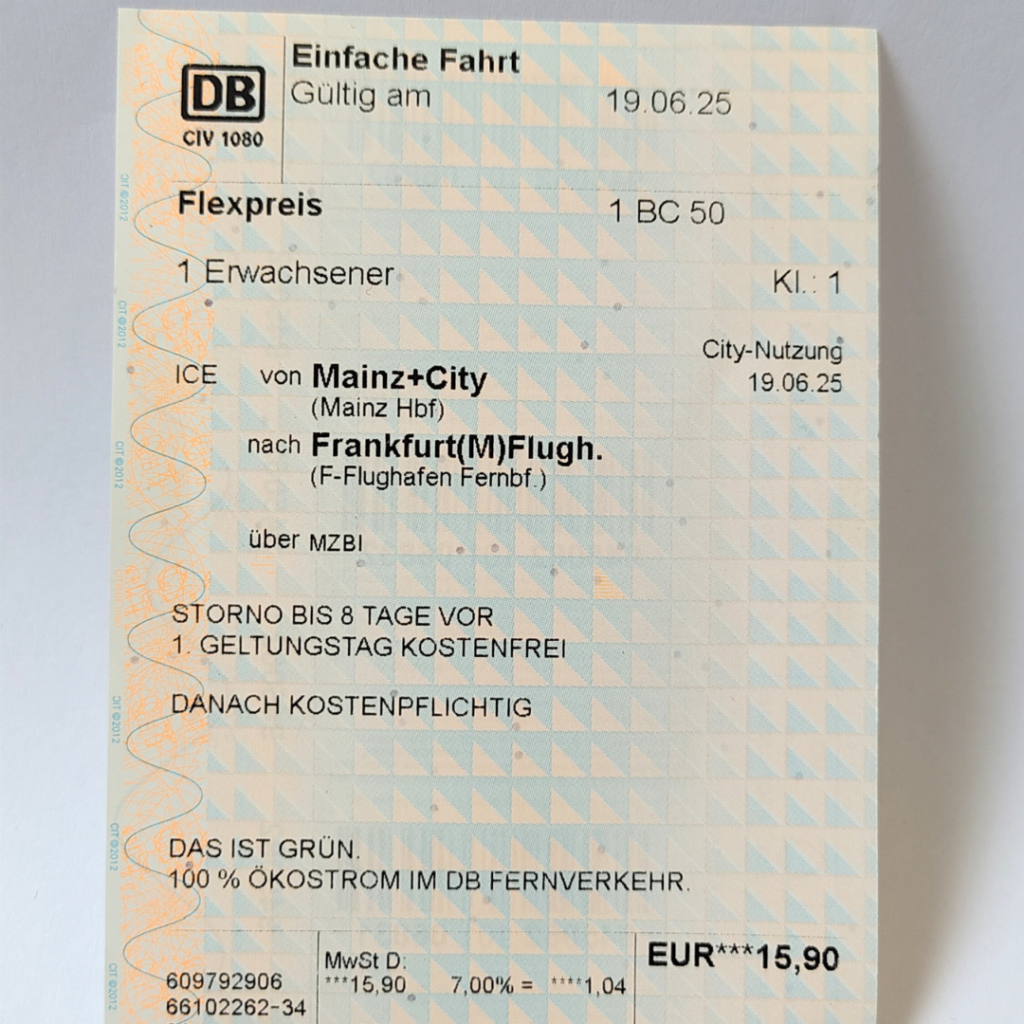

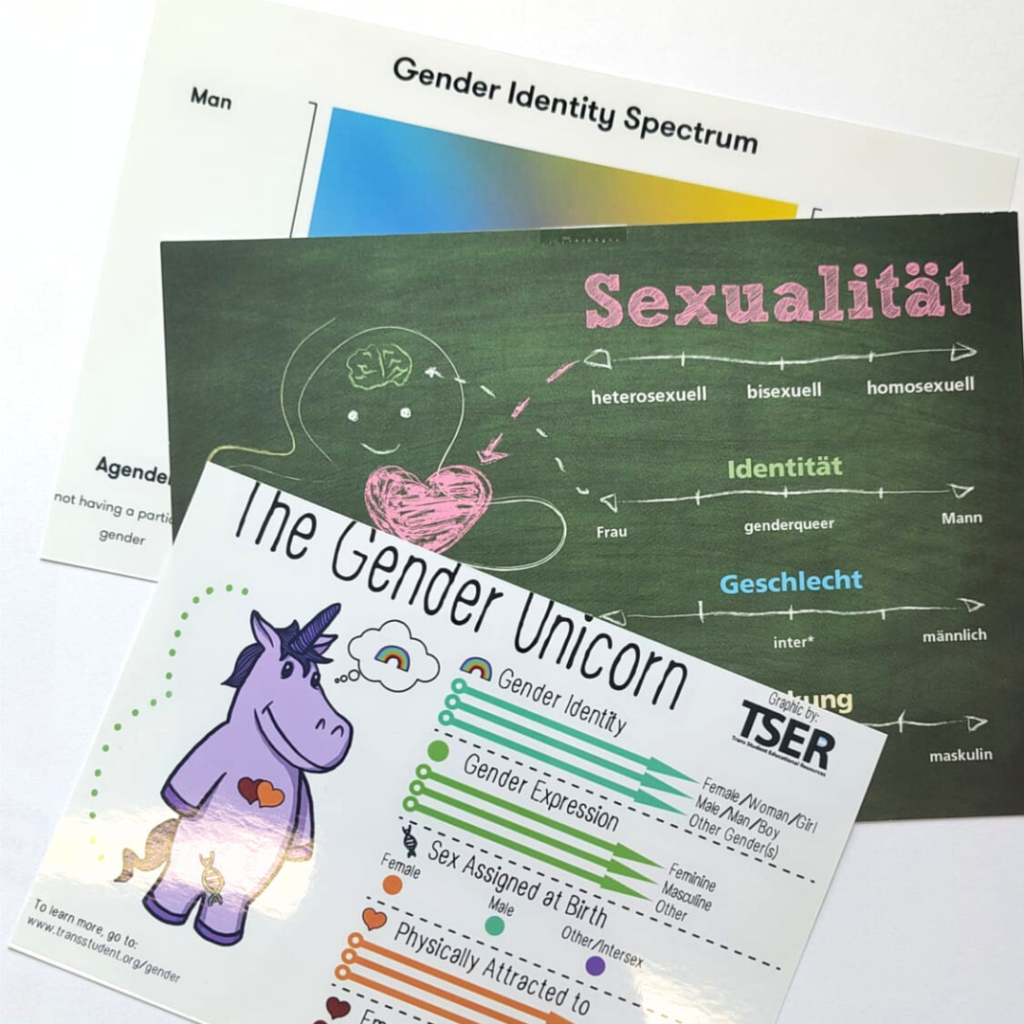

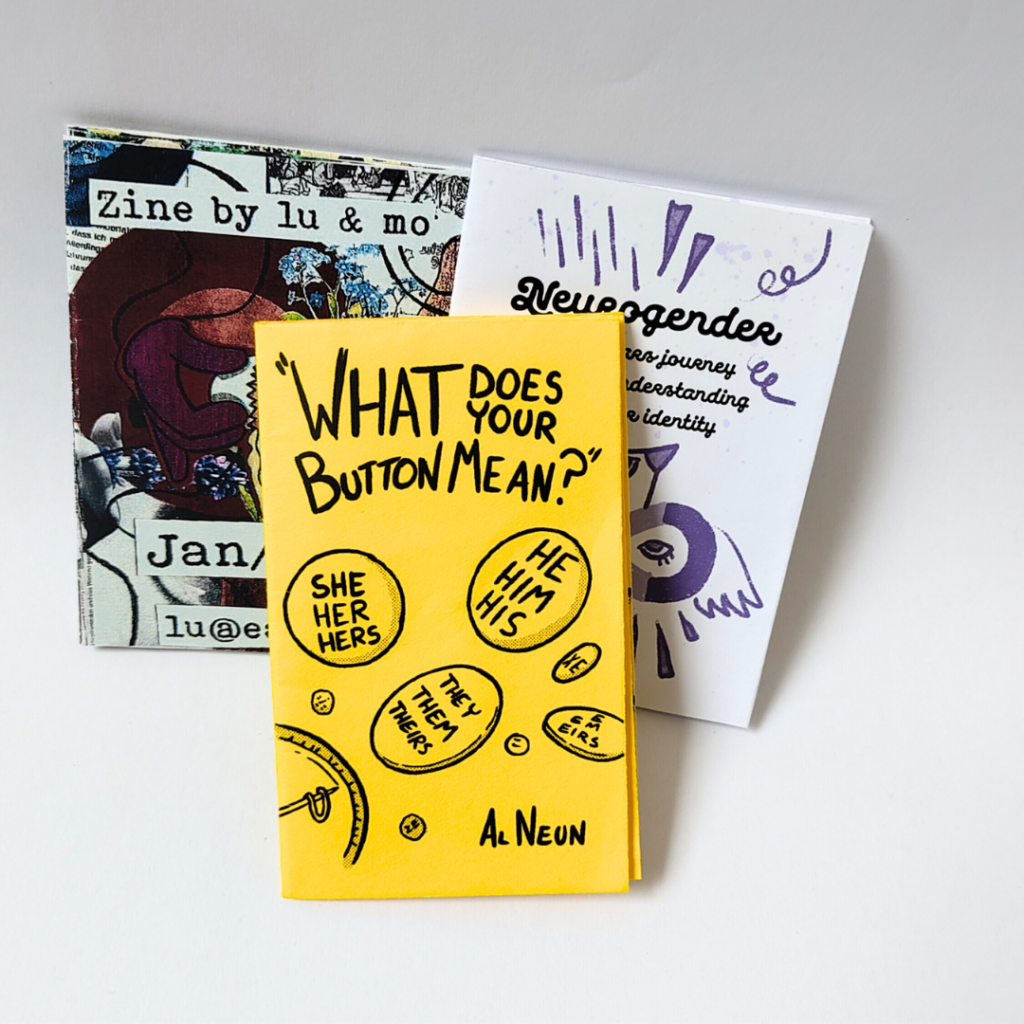

The type case is part of our exhibition "Menschen Sort[ier]en" in the "Schule des Sehens". Here you can find out more about the objects within. Type cases originally come from the printing industry – printers store the letters they use to typeset texts in these boxes. But they are also used in other areas to display the range of different specimens in a category – such as butterflies, insects or minerals. This type case doesn’t hold different specimens of the species Homo sapiens but different insights into our projects, ideas and food for thought. And because we could never depict all the types we sort each other to, we have left some of the compartments empty. The image shows, in which of our sliders you can find which object.